While the November note set out the argument of whether takaful should be treated as insurance, the December and January notes dwelled on the difference between takaful and insurance. In this February note I would like to go back to the issue of accounting. I will explore the determination of surplus in takaful and how this calculation may differ for accounting and for solvency.

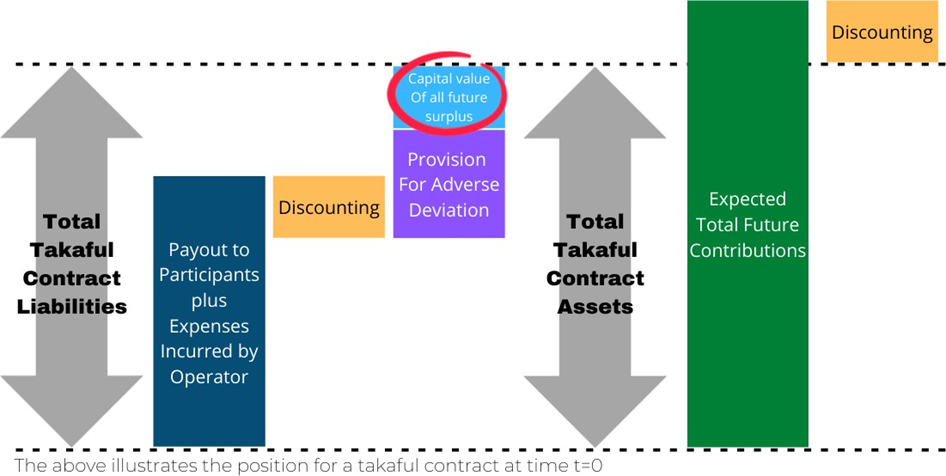

For the purpose of solvency computation Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) establishes the basis for determining the takaful funds’ actuarial liabilities towards the takaful participants. These liabilities are determined on a prospective basis, considering future income and outgo expected of the takaful certificate. In determining this liability there is currently no provision for future surplus distribution to either participants or the future performance fee payable to the takaful operator. What this means is that all future cash flows not required to meet the basic benefits (i.e. the guaranteed benefits and expenses) would be capitalize at time t = 0 as the present value of all future surpluses (see diagram below):

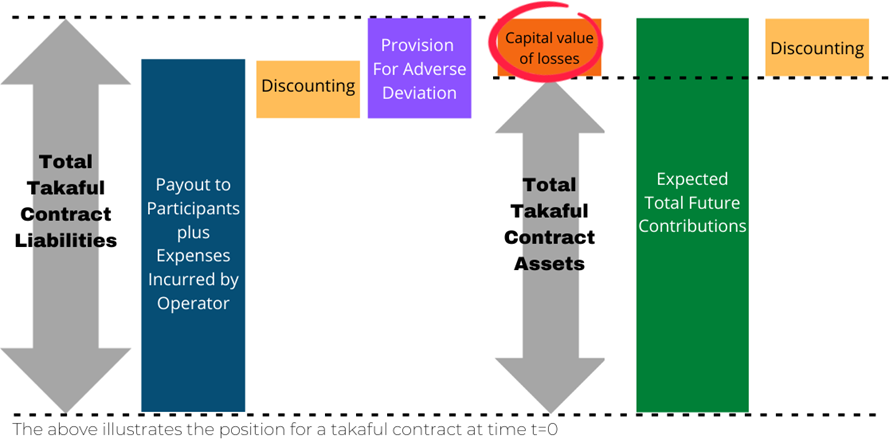

The above diagram describes what happens to a takaful certificate at the certificate contract level (not at fund level) when the valuation results in a surplus. The position would be different if considered at fund level (see later). There could also be certificates that show a loss; should that happen the revised position is illustrated below:

If for a moment we assume that there is no split of the contributions between the “expense” component and the “insurance” component, takaful will be exactly like a Mutual insurer, albeit a Mutual insurer with a separate shareholders’ fund. In such a mutual all the certificates are grouped together in the takaful fund and, in doing so, the surpluses underlying profitable certificates would offset the losses arising from other certificates. This operating model actually exists in Sudan as a Shariah compliant takaful operation. In such a model shareholders return are limited to investment earnings on the shareholders’ fund and any fees payable for managing the investments of the takaful fund. Specifically the shareholders are not entitled to any surpluses generated by the takaful fund.

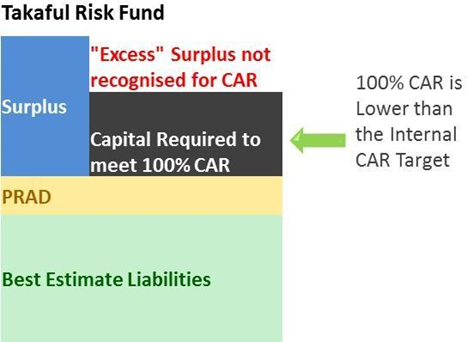

To reiterate, the diagrams above look at the profit or loss at the certificate level. For takaful in Malaysia the complication starts when each certificate is split into two distinct components, one being that which constitutes the wakala portion to meet management expenses and the other being the tabarru’ portion of the contract to meet risk related liabilities. In this process the surpluses and losses underlying the contract would accordingly be apportioned, however not necessarily in any consistent manner. Thus, while at the certificate level the profitability or otherwise of the certificate is clear, how the contribution is cut into the wakala fee and the tabarru’ will determine where and how much of the profit or loss would reside in the operator fund or the tabarru’ (takaful risk) fund respectively. For the takaful fund, the sum of all these tabarru’ values less the actuarial liabilities would result in a total profit or loss of the fund. In short total profit or losses in takaful is determined not at the certificate level but at the takaful fund level only. If a surplus arises, a distribution can be made to participants, and where allowed, the takaful operator as a performance fee. The allocation of this surplus is determined by each operator’s surplus distribution policy, and what terms have been agreed with the participants in their policy contract. Under the solvency computation basis, where the surpluses reside does not pose a significant problem (there is the small complication of how much surplus in the takaful fund can count towards solvency) as solvency is determined at the company level. The split of the contribution between wakala and tabarru’ does however determine where, when and how surplus emerges but the issue of whether the surplus or loss emerges in any particular manner is not a solvency issue, it is an accounting issue. Thus, currently, surplus is distributed on a cash basis even though effectively all surplus or losses that is being recognized for solvency have yet to be “earned”.

Now we turn to accounting under IFRS 17. IFRS 17 requires all expected profits under any one contract to be amortized (i.e. earned) over the contract duration while losses need to be recognized immediately. Due to its risk sharing nature this requirement however disappears when you consider a mutual. Mutual is defined here as an entity where the insureds are also the insurer. The underlying principle of a mutual is that losses underlying one policy can be carried by another policy which expects a surplus. Furthermore under a mutual not all surplus arising in a year need to be fully distributed, indeed they can also be set aside to be distributed to future policyholders. Thus surpluses in a mutual are determined at the fund level and may then be allocated back to the underlying policies, not unlike how surpluses are calculated at the fund level for the purpose of solvency computation. There is however one important difference under IFRS 17. Under IFRS 17 the net surpluses should be allocated systematically over the future years whilst under the solvency calculation all surpluses can be recognized and distributed immediately. This includes surplus attributable to premium income not yet received.

Currently there are suggestions that the portion of surplus in the tabarru’ fund expected to be distributed to the takaful operator as a performance fee should be accounted as a fulfilment cash flow in the operator fund. There are major difficulties with this approach as explained below (currently the performance fee to the operator cannot be more than the surplus distributed to participants or, put another way, is at most 50% of the total distributed surplus):

- The surplus to be distributed in the tabarru’ fund is determined at a total fund level. The surplus is never determined at the certificate level in takaful. Distribution of surplus at the certificate level therefore does not reflect the economics of the contract.

- Assuming the intention is to recognize the surplus at the total fund level, another complication arises as these surplus changes every time a new policy is included in the takaful fund.

- What happens if the certificate generates a loss, at the takaful fund level? Will there be a “negative” surplus share being credited to the operator fund? However this is not how takaful works, as “losses” in the takaful fund are shared between current and even future participants in the takaful fund. Assuming current and future surplus at the fund level is used to cover deficits first, this implies losses at the fund level will never be recognized at the operator’s fund level.

- The very reason that surpluses and losses are shared across current and future certificates within the same takaful fund makes it necessary to recalculate the distributable surpluses at each accounting period. Given that such redistribution is continuously assessed at fund level, it would not be possible with reasonable accuracy to factor surplus distribution to the operator as part of the operator fund’s fulfillment cash flows.

I will finish off this month’s note by going back to the solvency computation. Currently, there are indications that under a proposed revised statutory valuation methodology for the takaful funds, future cash flows should also include expected surplus distribution to participants and expected performance fee to the operator. The problems associated with such requirements outlined above for IFRS 17 would equally apply for the solvency computation should such a requirement be made. Currently, the statutory valuation liability does not factor in such surplus distribution, nor the expected future performance fees to the operator. Given that the purpose of the valuation is solvency, not the supportability of the current surplus distribution policy, such complications are best avoided.