Introduction

The need for insurance for the low income segment of the population is well documented. In this segment, an unexpected event resulting in a loss of income can have a catastrophic effect on the family unit. The problem with insurance is that it is usually run as a business and as such may be an inappropriate vehicle to service the low income segment of the market. Think about it this way, there are significant business risks in micro insurance and insurers in the developing world (where the low income segment of the market is probably the largest) see better business opportunities tapping the growing affluent middle income segment of the market. The risk-return story for this growing middle class in developing countries, where insurance penetration itself is still below that of more developed markets, is more compelling than for the lower income segment of the market. Thus, without government intervention in the form of subsidy or likewise, it is unlikely that the problem of underinsurance for the poor will be resolved anytime soon if we were to depend entirely on insurance companies to lead the way.

The insurance/takaful landscape

Insurance is one alternative to managing risks. For insurance this involves paying a premium for a transfer of risk from the insured to the insurance company.

For most individuals who buy insurance it is for the purpose of protecting assets. These assets can be property (casualty or general insurance) or future income (life insurance).

Insurance, like banking, is heavily regulated as this involves collecting money from the public and providing custodial services until claims are paid. Although there can be many forms of insurance (e.g. direct and re insurers) in most countries one set of regulations cover all insurers.

Successful insurance companies are those that have attained critical size (defined as when expense loading exceeds expenses incurred) and underwrite profitably. As a consequence of this the insurer is able to provide a good return to shareholders. The yardstick of profitability from the shareholders perspective is the unit return per dollar capital invested. Thus, the optimal position is to write the most profitable business for the least amount of capital employed.

There are potential conflicts of interest between the stakeholders (shareholders, sales agents, regulator and policyholders) in an insurance operation. In a proprietary company, the Key Performance Indicator (KPI) for management is maximizing the return to shareholders. This can lead to problems with mis-selling where consumers are sold products that they don’t really need. Excessive levels of underwriting profits can be a sign of mis- selling.

The curse of being “micro”

In most countries insurers serving the “micro” market also serve the “mainstream” market. Thus, maximizing profits to shareholders remains an important consideration for the “micro” market. In certain countries, like India, the regulator regulates that a minimum target of gross written premium should be from the “micro” market to ensure that the insurance industry contributes to the national agenda of financial inclusion.

A significant portion of the expenses incurred by the insurer in writing a policy is fixed in nature i.e. independent of the size of policy. So a micro (i.e. small premium) policy would have a bigger percentage of its premium allocated to meet expenses. From the insurers’ perspective this basis is technically sound but the insured would not necessarily be convinced that this is fair.

Regulations require that insurers keep sufficient free assets as contingent reserves to meet excess claims (defined as claims incurred in excess of risk premium collected). This ‘guarantee’ comes with a cost to the policyholder as shareholders need to set aside regulatory capital for each dollar of premium written. Solvency regulations usually do not recognize the unique nature of small policies, especially where the risks are geographically diversified, and so the amount of regulatory capital required for micro insurance may be excessive. There is therefore much to be said for having a regulation ‘lite’ for the micro sector.

Insurance is normally SOLD not BOUGHT and the level of financial literacy among buyers of micro insurance is probably low. The cost of providing financial advice is high as a percentage of the micro premium. Where then can micro policyholders afford to source financial advice on insurance? In the absence of personalized financial advice, the micro market should only serve simple and standardized protection products where minimal financial advice is necessary.

Profile of a “micro” policyholder

The potential “micro” policyholder is unlikely to have a stable source of income and, given the low average level of income, this means that he will have minimal savings.

He will also probably have a below average education standard. This would also imply a particularly low appreciation of the use of insurance as a risk management tool, in particular what to insure and what can be ‘self-insured’.

Other characteristics of a typical “micro” policyholder are:

- He is unlikely to have a bank account. Premiums will likely then have to be made on a cash basis, potentially increasing the cost of collecting instalment premiums.

- He is unlikely to own much in the form of assets. This would mean any one loss event can be financially ruinous to the family.

- He probably has limited access to healthcare, proper sewage and clean water and thus can be susceptible to poor health, leading to questions on insurability.

- For the hard core poor they will most probably be dependent on loans and government handouts to make ends meet from day to day. The ability to pay regular premiums is therefore in doubt. For others the level of disposable income may fluctuate greatly from month to month again affecting the ability to maintain a regular contribution towards insurance.

Given the above, micro insurance products would need to be ‘simple’ and ‘cheap’. ‘Simple’ means simplicity in design and simple to administer. Minimizing expenses means standardizing the process as much as possible, simplifying premium collection and claims payments, creating situations of automatic coverage to minimize the worry over anti- selection and minimizing the required number of points of contact between the insurer and the insured. It is perhaps more challenging to be ‘cheap’ given the possibility of limited statistics on the expected claims experience for this segment of the market. The answer perhaps is to build in margins but allow any surplus to be distributed back to the policyholders in one way or another.

Conventional products – breaking the premium into its components

It is instructive to analyze the composition of a typical insurance premium according to the size of premium. To do this we split the total premium expected to be paid over the average policy duration by its utilization expressed as a percentage of Annualized Premium Equivalent (100% = 1 year’s APE). As an example if 200%APE is used to pay commissions it means two years premiums are used to meet the commission expense.

We first consider the composition of a 20 year conventional term assurance policy. This policy pays the insured amount only if the insured dies within the policy term. Now even though the policy is for twenty years, as a result of lapses and surrenders, the average policy duration is actually shorter. In fact in this example the average duration of the policy allowing for lapses and surrenders is only 6.3 years.

| APE Size USD | Management Expenses % APE | Distribution Cost % APE | Benefit Cost % APE | Profit % APE |

| 183 | 113 | 131 | 242 | 139 |

| 626 | 66 | 131 | 252 | 176 |

| 1748 | 53 | 131 | 330 | 110 |

What the above table says for example, is that for a policy with an annual premium of USD183, slightly over one year’s premium (113%) is utilized to meet management expenses. In contrast slightly less than two and a half (242%) years of premiums are used to pay claims. Thus, the actual amount utilized for the insurance payout ranges from only 38% to 52% of the total premiums collected with the smaller premium size policy paying out the least percentage-wise in the form of claims.

We now consider a 20 year conventional endowment policy where the average duration of the policy allowing for lapses and surrenders is 6.5 years. Unlike a term policy, an endowment policy also pays out the sum assured should the policyholder survive the contract term.

| APE Size USD | Management Expenses % APE | Distribution Cost % APE | Benefit Cost % APE | Profit % APE |

| 76 | 220 | 132 | 381 | -78 |

| 348 | 85 | 132 | 416 | 21 |

| 687 | 67 | 132 | 421 | 35 |

The average amount of total premiums collected paid as claims is slightly higher here. The actual amount utilized for the insurance payout range from 58% to 64% of premiums paid, again with the smaller premium size policy paying out the least percentage-wise in the form of claims. In this particular example the insurer is expected to make a loss on the smallest premium.

The ‘spirit’ of Takaful

Islam is not only about belief in God and how God should be worshiped. Islam provides guidance on all aspects of life, from resolving family matters, to crime and punishment and to the conduct of business. Insurance, as a business therefore needs to satisfy the conditions placed by Sharia for it to be considered halal (permissible).

Islam is not against profiting from trade and services but Sharia principles require that such transactions should avoid exploitation of the individual. This means avoiding riba (interest), gharar (uncertainty in the contract) and maysir (gambling). This applies to both the insurance contract and how insurance funds are invested.

The 1985 Fiqh Academy in Makkah concluded that the conventional for profit insurance contract has elements of gharar and maysir making it not Sharia compliant. For insurance to be halal it must satisfy two conditions;

- It is cooperative in nature (this means that insurance must follow the cooperative or Mutual model).

- The insurance risk pool has to be established on the basis of charity and cooperation (the opposite of charity and cooperation would be an institution driven by profit).

The Fiqh Academy reasoned that a more acceptable form of insurance is the cooperative or Mutual model where the intention is to foster solidarity, all members in the group lending a helping hand to those in the group who are unfortunate. The gharar element it would seem is offset by the intention of mutual assistance among the participants in the cooperative, while the maysir element is removed by removing the emphasis on profiting from the program.

Takaful and micro takaful in Malaysia

In Malaysia, takaful is a hybrid, a combination of proprietary (the operator’s fund) and mutual (the participants’ fund) operations. The ‘insurance’ is conducted in the participants’ fund. All takaful operators are from 2014 subject to a Risk based approach to solvency capital requirements. The Regulation places the onus on the operator to guarantee that takaful benefits are paid. The operator provides a temporary qard (interest free loan) to cover any deficits in the participant’s fund which is then repaid from future surpluses in the participants’ fund. Micro takaful products in Malaysia are primarily designed as “small size” regular takaful products subject to the same considerations with regard to profitability/sustainability as other takaful products. Usually takaful is packaged with small loans to save on distribution costs. In Malaysia therefore, it is more “mini” takaful rather than “micro” takaful.

What about takaful product?

The need to ensure transparency means the deduction for expenses and commissions must be clearly set out. This deduction, called the agency or wakala fees, is paid to the takaful operator to meet its distribution and management expenses. Currently the wakala fee charged by the operator is expressed as a percentage of the contributions (i.e. premium) not a fixed dollar amount. Whether the policy is ‘regular’ or ‘mini’ the wakala fee as a percentage of contribution is unchanged. Thus the percentage of contribution paid out as claims (which is total contribution less the wakala fee) is independent of the size of the contribution. In the example for the conventional term and endowment policies given earlier we saw that the percentage that actually goes towards paying claims vary by size of premium.

The existing Takaful Model can be considered as Takaful Tijari (Business). The diagram below describes the business process.

In Malaysia the operator is also allowed a share of the surpluses arising from the Participants’ Pool. This practice is controversial from the Sharia perspective but is seen by the regulator as a means to partly align the interests of both the shareholders and the participants.

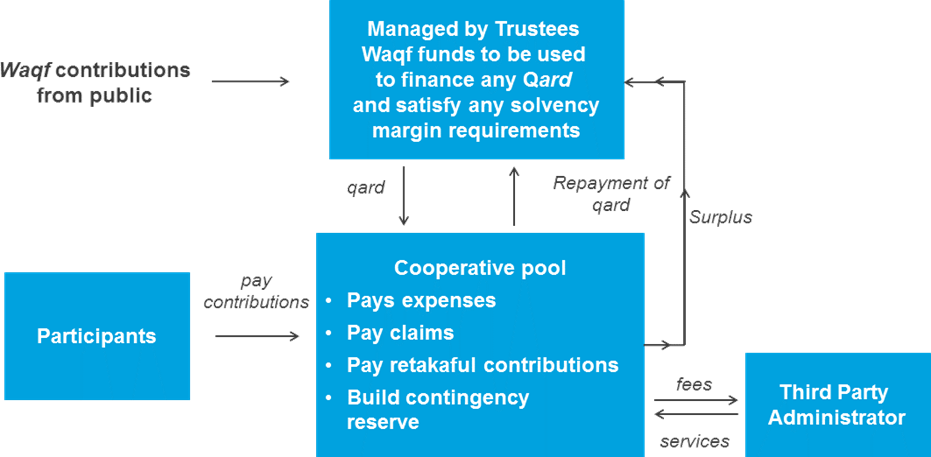

Should we use this same Takaful Model for the “micro” segment of the insurance market? The Islamic economic system is anchored on the needs of the community over the needs of the individual. Indeed for a Muslim his wealth is not his but has been given by God to be held in trust for the benefit of the community. It is said that only that part of his wealth that he gives away as charity is his. Apart from sadakah (charity), the other two means of achieving the objective of an equitable society are through the payment of zakat (tithe) and waqf (endowment). Zakat is an annual ‘tax’ put on idle capital (assets which have not been put to productive use for a period of one complete lunar year) while waqf is an endowment made by the individual for the use of the public good. How can the resources obtained through zakat and waqf be used to support the micro takaful industry? The diagram below suggests an alternative model to the Tijari model, one where one stakeholder is removed from the equation (the shareholders) and replaced with another, the trustees. We term this alternative model Takaful Ta’awuni (or the cooperative model).

The proposed model is not immune to the other problems besetting micro insurance. While the need to satisfy shareholders’ profit expectations is removed there are expenses to control and processes that need to be optimized to ensure the model is workable.

How can we minimize charges for expenses and distribution costs for the micro product? This requires a simple product design, perhaps with one fixed sum assured and with no underwriting requirement. Where the claims incidence is low (for example, life insurance where a benefit is only payable on death) costs would be minimize by having a simple claims procedure. This product will probably be ‘group’ products, i.e. aimed at a specific group of individuals with common or shared characteristics. Distribution costs can be high as a percentage of premiums collected (in the example given earlier distribution costs amounted to 131% of APE) and should this be eliminated, or at least minimized, it can reduce the premium significantly (by 20% in the earlier example).

To minimize distribution costs the plan will ‘ride’ on any existing commitments (e.g. included in the loan repayment instalment, built into the price of fertilizers etc.). If possible, use community rating (one rate for all). Any surpluses are automatically treated as a contribution to the waqf fund. This would allow solvency capital to grow with the business and also to save in the administration costs incurred should surpluses be instead distributed. An alternative use of any surplus is to spend the surplus for the benefit of the community as a means of promoting solidarity. For example it can be used to provide scholarships to the children of the community. It can also be used for the purpose of creating awareness of the benefits of the micro takaful scheme.

These conditions are already present in a cooperative structure e.g. farmers co-op, police co- op etc. Under existing cooperatives there already exist the necessary infrastructure for premium collection and benefit payouts. This is not significantly different to the structure of many small mutuals and cooperatives that had previously existed in the UK before the introduction of high capital requirements.

It is important to specify that benefits payable under the takaful program are not guaranteed; instead it is based on what funds are available e.g. if funds are inadequate benefit payouts will be proportionately reduced to ensure sufficient funds to pay all claimants. This condition is important, as although the intention is to pay full benefits, explicitly guaranteeing payouts would probably attract comparisons with the formal insurance sector and this will ultimately make the takaful entity subject to stringent capital and operational requirements. In this sense it is vital that regulations acknowledge the non- guaranteed nature of payouts and allow for much lower capital requirements.

Discretionary Mutual – An Australian Innovation

The conventional insurance arrangement is not the only means to manage risk currently available. In Australia for example there is the Discretionary Mutual Model. This is formed by a cooperative (e.g. Capricorn Mutual). To be accepted into the insurance program you must be a member of the founding cooperative. The Discretionary Mutual is not regulated by the Insurance Regulator in Australia and insurance benefits are not guaranteed. The Board of Directors decides on the payment to be made on receipt of a claim. It also decides on whether to accept applications for membership and on the insureds’ level of protection.

The Board in making its decisions will be guided by the principles of fairness and justice. For example, it may decide to pay a claim which if it had been insured, the insurance company may not have paid. The lack of regulations is helpful in reducing cost although it does point to the need for strong internal corporate governance.

In summary

Given the level of transparency practiced in takaful it is proposed that micro takaful rather than micro insurance is more suited for the micro segment of the market. The micro takaful organization would be based on a cooperative model rather than the hybrid takaful model.

Furthermore where possible, consideration should be given to the use of waqf money to provide for the capital necessary to establish the micro takaful operation. Consistent with the concept of a waqf, these funds should be managed with the intention that it will be preserved over time notwithstanding that these funds may be temporarily drawn down by the participants’ fund to meet temporary deficits due to fluctuating claims experience. Indeed it should grow as it is ‘fed’ by surpluses from the micro takaful operation. This waqf would be managed by suitably qualified trustees in place of a Board of Directors.

Expenses for the operation can be minimized by standardization of benefits and contributions and the use of a third party administrator. To ensure that the poorest are covered and instalment premiums are paid on time, consideration should be given to utilize zakat money to subsidize the contributions on behalf of the poorer participants. This would mitigate the effect of the uncertain income flow experienced by the poor which in many instances means that the lapse experience among micro insurance policyholders may be exceptionally high.

Finally, to avoid being labelled as an insurance operation, benefits should not be guaranteed (i.e. similar to a discretionary mutual). This will avoid punitive solvency requirements and expensive regulatory oversight. Nonetheless, on a voluntary basis the Trustees must ensure that best practices in corporate governance are maintained. A holistic approach with the support from the government, particularly in terms of legislation and the appropriate capital requirement, is essential for the successful development of a micro takaful market.

If you have any queries on the above please do not hesitate to contact: