IT IS WIDELY ACCEPTED that insurance plays a very important part in commerce and personal finance. While most may take insurance for granted, many people of the Muslim faith find that conventional insurance is incompatible with their religious belief. In the late 1970s in Sudan, and the 1980s in Malaysia, the concept of Islamic insurance, or takaful, was introduced.

Though its acceptance in the Muslim world was slow at first, the new millennium has seen a quick- ening in the pace. This has a lot to do with the emer- gence of a young generation of educated and affluent Muslims seeking a substitute for an important part of commerce and personal finance. For Muslims, Islam is not merely about how to go about worship- ping God; it is also a way of living life.

This article looks at the theory behind takaful through the eyes of an actuary. I have done this by first identifying the various facets of insurance—in- vestments, the insurance contract, and the under- writing of risk—and explaining how these concepts apply under takaful. But first, I must address the ba- sic law of Islam, Sharia, under which takaful exists.

Islamic Religious Law (Sharia)

Agreements between individuals and commercial un- dertakings cannot exist without the basic rule of law. Islamic religious law covers not just the practice of religious worship but also how Muslims should live their lives and, by extension, conduct commerce.

This law is conveyed through the Quran (the holy book that Muslims believe to be the direct word of God) and the Prophet Muhammad’s Sunna (which documents the spoken advice and acts of the prophet, also called the hadiths). While the Quran has not been changed since it was first compiled into written text soon after the prophet’s death, this is not the case in the recording of the Sunna. The Sunna was passed on through generations after Prophet Muhammad’s death in A.D. 632 before being systematically compiled and authenticated in various degrees. Notwithstanding the process of authentication, there may remain doubts about whether some Sunna can be directly attributed to the prophet himself.

Where the law is ambiguous, or if a new situation should arise, the interpretation of Islamic law is left to a council of Sharia scholars called the ulama. They, in turn, rely heavily on the Quran and the Sunna in their deliberations. It’s not unknown for Sharia scholars to disagree with each other over certain interpretations of the law or even to change their minds on an issue over time.

Investments and Interest

In Islam, the basic principle of investment is that re- ward must be accompanied by risk. On this basis, it’s permissible for a Muslim to invest in Sharia-approved stocks (meaning, for example, no gaming, brewery, tobacco, or highly leveraged companies) as prices of equities and dividends from equities command no cer- tainty in value. A stock investor is subject to market risk. Investment in bonds, however, where there are capital protection and fixed returns, is not permissible. Yes, there is risk of default, but this is credit risk. Credit risk on its own is not permissible in Islam, as that is the foundation of interest.

Contrary to widely held beliefs, Islam does not reject the notion of the time value of money. Islamic scholars generally accept that goods sold on credit are priced higher than goods sold for cash. Islam, however, does prohibit the charging of interest (or riba) on loans. Specifically, in Islam, money cannot be treated as a commodity to be bought or sold but rather only as a medium of exchange. As an exten- sion of this, financial assets can’t be sold or used as collateral. In Islam, therefore, an entity cannot refi- nance receivables because they’re not real assets. A hadith attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, “Every loan that attracts a benefit is riba,” defines the ban on interest in Islamic finance.

In Islam, instead of leaving the terms of the contract to be determined by the parties involved, contract law is expressed as rules for various kinds of contracts.

Commercial Contracts

Modern contract law accepts any commercial agreement as long as it’s not unlawful. In Islam, instead of leaving the terms of the contract to be determined by the parties involved, contract law is expressed as rules for various kinds of contracts.

Put simply, Islamic contracts are specific in nature (i.e., they are contract types). For example, there is an Islamic contract for trading (bay’) and one for lease (ijarah). By agreeing on the type of the contract for a particular transaction, the rights of the various parties to the transaction are automatically understood. A question that will naturally arise, then, is whether one can create a new Islamic contract where no suitable Islamic model is available. Any contract to be lawful in Islam must abide by a certain set of rules and principles. In particular it should:

- avoid riba (usury);

- avoid maysir (gambling);

- avoid gharar (risk or uncertainty).

While usury and gambling are forbidden, depending on the circumstances, a certain element of gharar is acceptable.

The conventional insurance contract violates the rules against riba and gharar—the former because most insurance companies have, as part of their assets, interest-bearing investments; the latter because of the basic nature of the contract itself.

The maysir aspect in modern insurance was removed early on in its development by the introduction of the concept of insur- able interest. However, insurable interest itself, though clearly attributable, may not always be clearly quantifiable. Therefore, any insurance contract that can result in a financial gain to the insured would also run afoul of the ban against maysir.

The following paragraphs provide samples of contract types in Islam that are referred to later in this article, together with a brief explanation.

Mudharaba. This contract defines a type of partnership. Un- der mudharaba, some of the partners in the contract contribute only capital while the other partners contribute only labor.

If the partnership results in a profit, all partners in the con- tract share in the profits at an agreed-upon percentage. How- ever, should there be a financial loss, only the partners con- tributing capital would bear it, limited to the amount of capital invested in the venture. Therefore, in a mudharaba contract, those partners contributing labor only lose their labor should the venture prove unprofitable.

Wakala. This contract defines an agency. Simply put, under wakala, one person represents the other as the latter’s agent. Therefore, in exchange for compensation, which can be a certain percentage of the consideration or a fixed amount, the agent performs a certain service.

Qard Hassan. This is a gratuitous contract. Qard is the loan of fungibles of which the most obvious is, of course, money. The rule against riba means that the loan must be free of any form of compensation. The term qard hassan (literally meaning “good loan”) describes an interest-free loan of a monetary kind.

Sadaqa. This is another gratuitous contract. It literally means alms, or charitable donations (also known tabarru’).

The challenge, then, is how a takaful contract can be struc- tured within the context of Islamic law. The creation of a new type of contract specifically for insurance would be an obvious route. This contract would then also have to follow the three basic rules and principles set out earlier. In order to ensure wide acceptance among Muslims, however, the preference is to use the existing Islamic contracts, in combination if necessary, to make takaful work.

The Underwriting of Risk

This is what makes insurance different from other commercial contracts. I would define underwriting risk as the transferring of the responsibility for paying losses from one person to another person or entity.

What is the ulama’s objection to this? The basic objection is the presence of gharar in the insurance contract. Gharar, as explained earlier, is the presence of risk or uncertainty. We have seen that market risk is perfectly acceptable in Islam, while credit risk on its own is not. Commercial trade with its under- lying risk of a loss and benefit of a profit is also acceptable in Islam. Then what makes underwriting risk unacceptable?

If we examine the underwriting contract, we see the insured agreeing to pay the insurer a premium in exchange for the in- sured transferring his risk of a financial loss to the insurer.

Should this risk be realized during the tenure of the con- tract, the insurer will indemnify the insured. If we look at this contract from the perspective of the insured, we see that in exchange for a premium, he may or may not receive a service from the insurer. The service here is the indemnification of a loss by the insurer. Should the tenure of the contract expire with no claim, the insured forgoes his premium.

One interpretation of this is that the insured has received a service from the insurer because, had a claim occurred, he would have been indemnified of his loss. Another interpreta- tion (and this would be the Ulama’s interpretation) is that this contract has an element of uncertainty in which the service (the indemnification of a loss) may or may not be forthcoming.

How can this objection be overcome in Islam? The Islamic Fiqh Academy, emanating from the Organisation of Islamic Conferences, convened in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in December 1985 to consider all available types and forms of insurance. It subsequently decreed that insurance, through the concept of a cooperative (which is founded on the basis of tabarru’ and cooperation), is acceptable in Islam.

Under the concept of a cooperative, the participants (poli- cyholders) in the pool agree to jointly indemnify each other against a loss. Effectively, the insured is also the insurer in a cooperative insurance pool. Gharar is still evident in this con- tract, but it’s forgiven because the contract is made on the basis of mutual self-help and cooperation. As the reader will see later, the concept of tabarru’ is applied to overcome the problem of gharar.

Takaful in Malaysia

Unless there is already a bond between the individuals in a group—through an association, for example, or through an af- finity group—it’s laborious to set up insurance as a cooperative. There is also the issue of where the initial start-up capital would come from and who would manage the takaful entity. In 1985, the first takaful company in Malaysia was set up under the concept of mudharaba. This company, Syarikat Takaful Malaysia (STM), was a composite entity writing both family (i.e., life) takaful and general (i.e., casualty) takaful. It was initially capitalized at RM10 million (approximately $2.6 million). The set-up consisted of three separate statutory funds. There is the Takaful Operator’s Fund (i.e. shareholders fund where the capi- tal resides), the Family Takaful Fund (for the life business), and the General Takaful Fund (for the property/casualty business).

Most important, this company underwrote takaful business at a technical level that is comparable to conventional insur- ance. This meant charging contributions (i.e., premiums) that were calculated based on appropriate risk factors and published mortality tables where appropriate. An actuary is required to sign off on any family takaful products. STM’s Sharia scholars accepted that to be fair to the participants, the contribution must be scientifically calculated. Prudent underwriting stan- dards were imposed to either exclude impaired or substandard risks or to charge appropriate additional risk contributions.

The operational difference between conventional insurance and takaful as practiced by STM lies in the investment of the assets and the treatment of expenses and surplus. All investments were made in halal (permissible) assets. In addition, in STM, all man- agement expenses were charged to the Takaful Operator’s Fund. Only direct expenses (medical underwriting fees, for example) were charged to the participants. In exchange for the labor of set- ting up and managing the takaful operation, the takaful operator is entitled to a share of the profit on investment (defined as the income earned on assets invested) and to a share of the surplus that arises from the underwriting of the business.

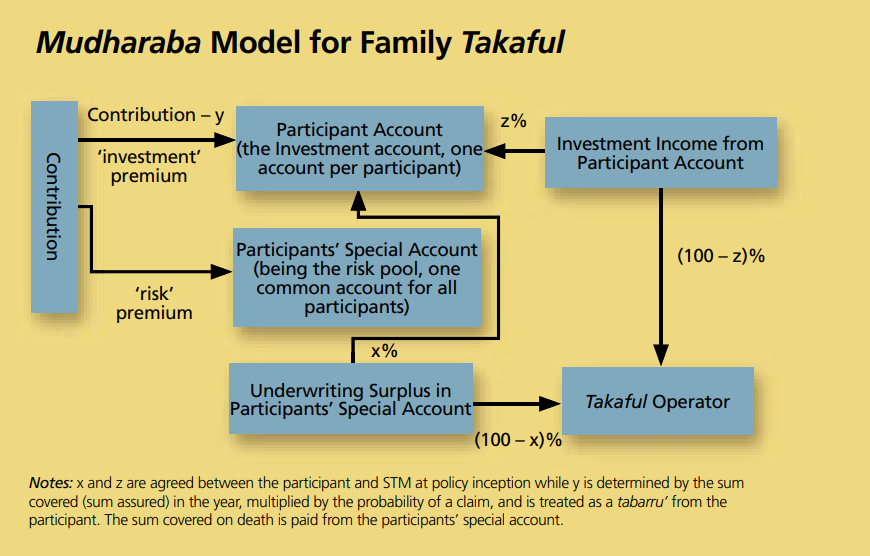

The following chart explains how the takaful operation is conducted by STM for family takaful.

Mudharaba Model for Family Takaful

On the maturity of the contract or early surrender, the partici- pant gets the amount accumulated in his participant account. At his death, his beneficiaries get the sum covered, in addition to the amount accumulated in his participant account.

As explained above, the underlying Islamic contract here is the mudharaba. A mudharaba contract consists of the capital provider (the participant) and the service provider (the takaful operator). The service provider manages the operation in return for a share of the surplus on underwriting and a share of the profit from investments. The takaful operator doesn’t share in any losses; he puts only his labor at risk. However, if there are losses in the risk pool, the takaful operator provides an interest-free loan (qard hassan) that has to be repaid when the risk pool returns to profit- ability and before any future surplus is distributed.

How does the takaful operator profit under this model? His income derives from a share of the investment income and a share of the underwriting surplus. He makes a profit when this income exceeds his expenses. Management, therefore, has to determine the appropriate percentage of investment income and underwriting surplus to share, which will cover his ex- penses and service his capital. The participant then agrees to the percentage when the takaful contract is signed. The role of the shareholders’ capital is to meet the expenses of running the company and, where necessary, to provide a qard hassan should a deficit in the risk pool arise.

What are some objections to this takaful model? Some Sharia scholars object to the appropriateness of the mudharaba contract. The basis of the mudharaba contract is profit sharing, not surplus sharing. The fact that the participant’s capital (specifically that portion representing the risk premium) is being used to pay claims means there is no profit in the transaction. In Islam, profit is defined as the increase in total value of the investment in the venture over the initial capital employed. This may be semantics to some, but it’s an important issue to Sharia scholars.

The sharing of the underwriting surplus by the takaful oper- ator may also give rise to objections from some Sharia scholars. However, other Sharia scholars point out that the risk premium is treated on the basis of a tabarru’ (charitable donation) and therefore provides for the operator to dispose of the surplus as he deems fit.

The Alternative Model

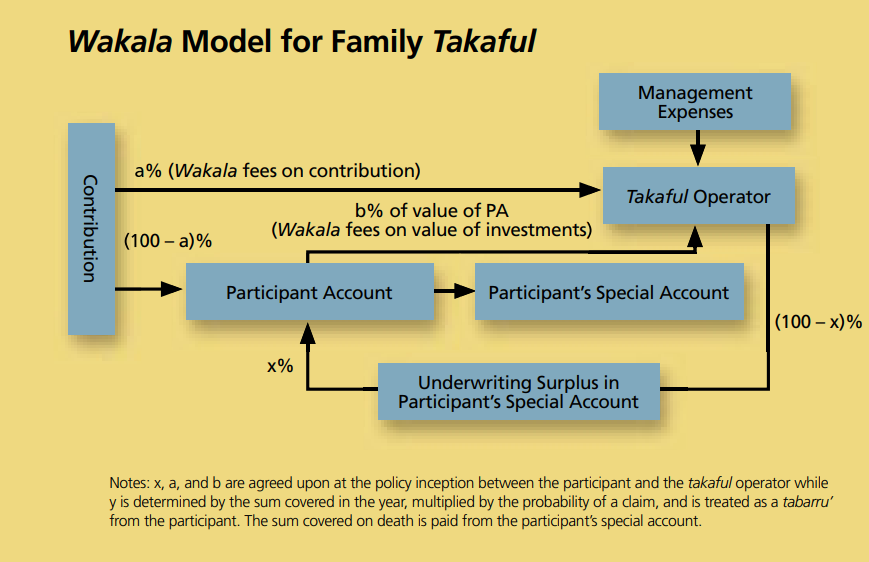

In 2003, the fourth takaful company in Malaysia was established (Takaful Ikhlas). This takaful company employed the concept of the wakala contract. Here the takaful operator acts as an agency

on behalf of the participants. In return for the services rendered, the operator is paid an agreed-upon predetermined fee. This fee can be a percentage of the contribution (i.e., total premium) or an absolute amount. There is a fee on the risk portion of the contribution (a general management fee) and a fee on the investment of the contribution (a combination of general management fee and asset management fee). The following diagram explains a simplified form of the wakala model for family takaful.

Wakala Model for Family Takaful

Similarly, on the maturity of the contract or early surrender, the participant gets the balance in his participant account. If he dies early, his beneficiaries get the balance of his participant account, plus the sum covered, which is defined at the beginning of each year or month.

Should there be a deficit in the participant’s special account, the operator would extend a qard hassan to be repaid before any future surplus distribution.

How does the operator profit under this takaful model? The risk premium is paid regularly from the accumulating partici- pant account. Management expenses are again met solely by the operator. The operator is compensated by the wakala fees. In the example, this is expressed as a percentage of the contribu- tion and a regular percentage of the value of the accumulating investments in the participant’s account. Contrast this with the mudharaba model where the operator’s income derives from the surplus on underwriting and profit on investments.

Obviously, if there’s no surplus or profit, the mudharaba contract produces no income for the operator, while under the wakala model, there will always be some income because the operator’s remuneration is based on capital, not income.

Purists would favor the wakala model over the mudharaba model because the agency concept as applied to takaful is con- sistent with that contract as applied to other businesses.

It should be highlighted that both takaful models depend on the concept of tabarru’ to overcome the gharar factor under the risk aspect of takaful. Effectively, the Ulama rules that if the risk premium is donated to the participant’s special account (risk pool), it’s a gratuitous contract where gharar doesn’t apply. The debate, then, is whether any surplus in the special accounts should be returned to the participants or paid as a performance fee to the operator.

Open a new door every day.

Aetna is a leading provider of health care coverage and related benefits, and we are committed to giving people information so they can make more informed health care decisions. We are looking for smart, ambitious, enterprising people who can help us continue to build the new standard in the industry every day. People who work hard and hold themselves accountable. People who are ready to leverage the power of what they know to make a measurable difference. Now is the time to believe in the value of your work. Get ready. Come work with a team of proud, open- minded, diverse people who are driven to make a positive impact. Every day.

In Takaful Ikhlas, the operator takes only a small percentage of the underwriting surplus, and this is considered a handling fee rather than an expected major source of income to the op- erator. The underwriting surplus the operator doesn’t take as a fee is usually also given away to charities rather than returned to the participants, unless the amount is deemed significant.

Also, all charges, fees, and profit sharing percentages in both takaful models are declared at the outset of the contact and are therefore totally transparent to the parties involved. This is con- sistent with the concept of avoidance of gharar in Islamic law.

A takaful operator is not limited to only one takaful model in its operation. Recall that it’s not the method of how takaful will be conducted that’s at issue, it’s which Islamic contract to apply in the commercial venture. STM, for example, also uses the wakala contract in its operation for a range of family taka- ful products where the participants choose how the savings component of their contribution is to be invested.

The Future of Takaful

Not by any means has the development of takaful been limited to Malaysia. Sudan deserves credit for first attempting takaful, while the wakala model, as developed for family takaful, was actually first implemented in Saudi Arabia by Bank Al-Jazira’s Takaful Ta’awuni division. Malaysia, however, deserves credit for having assisted in setting up takaful in many Muslim countries, including Negara Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Saudi Arabia, among others.

If asked to describe takaful as simply as possible, I would describe it as comparable to a mutual insurance operation in which the mutual’s investments conform to the requirement of Sharia. That would define the organizational structure. To that must be added that the mutual’s product lines would also need to observe the ban against maysir.

In this article, I have concentrated on takaful as a concept. What is even more exciting is the potential role of takaful in Islamic finance and investment. The ban against riba has ef- fectively restricted the role of Islamic banks in the financing of business. The problem is one of mismatch of assets against liabilities. Banks are conduits for short-term deposits. Islam’s requirement that reward can come only with risk, while forbid- ding riba, means that the Islamic bank’s liability will be long term because banks will effectively hold equity in the invest- ments they make with the depositors’ money.

Due to the issue of mismatching of deposits to investments, many Islamic banks are more akin to investment banks than commercial banks. The money is in the masses, however, and accumulating a small number of deposits over a large popula- tion results in a large amount of money. Muslims make up more than one billion of the world’s population. The Muslim world is generally under invested and financially underdeveloped. It sports a young demographic profile with an increasing purchas- ing power and savings potential.

All this points to a huge potential for long-term savings and in- vestments. I believe takaful, if developed and marketed effectively, has the unique ability to tap into this potential. Here, the asset and the liability match. Savings through family takaful for retirement in particular would provide a valuable pool of long-term savings, ready for the right investment opportunity to arise.

On a final note, the reader may question whether Islamic finance and institutions are reserved only for Muslims. The experience in Malaysia, where over 40 percent of its population is non-Muslim, shows otherwise. A significant number of those who use the facilities of Islamic banks and takaful companies are non-Muslims.

Even in non-Muslim countries, the response to takaful among non-Muslims is encouraging. For example, in Sri Lanka where less than 10 percent of the population is Muslim, some 15 percent of the policyholders of the sole takaful company there are non-Muslims. If Islamic finance and takaful are to suc- ceed globally, they will succeed not because they are approved by Sharia, but because they provide an alternative means of savings, investment, and finance to that which is currently available.