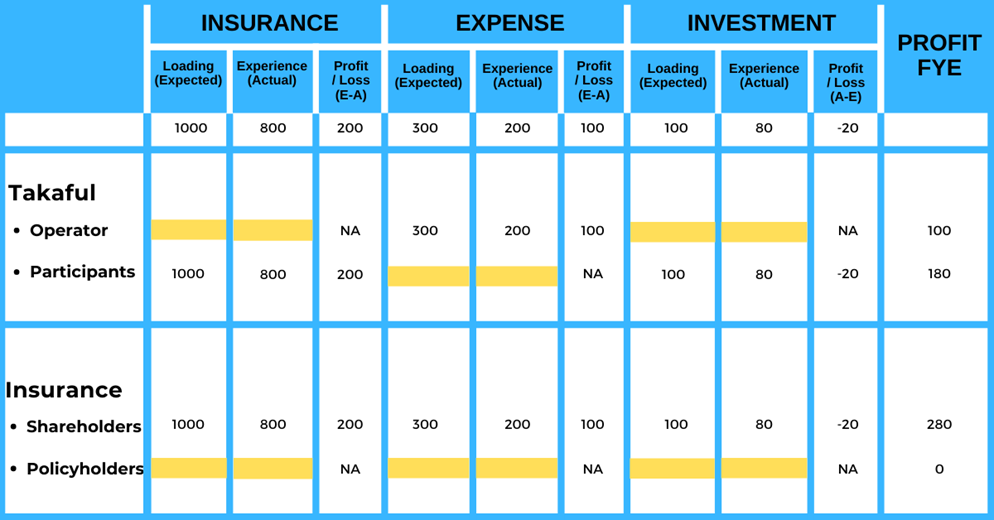

I finished off the November note on “Where are we now on the application of IFRS 17 to takaful” by making an observation that, first things first, the various stakeholders need to agree on the basic principles of takaful and the difference between takaful and insurance. This December note tries to make that distinction clearer. A word of caution though, that what applies in Malaysia would not necessarily apply in other countries. There are subtle but important differences in the way takaful is practiced across countries which can result in different economic outcomes.

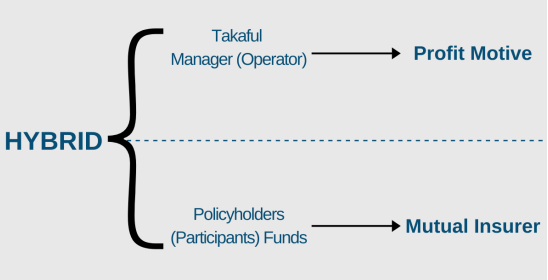

Takaful is fundamentally a Mutual Insurance but only when the Mutual Insurer’s investments are in Shariah compliant investments. Mutual Insurance has been around for over a hundred years, so takaful isn’t actually anything new. Why modern takaful is not structured exactly like a Mutual Insurer can be summarized in one word, “Capital”. In the world of IAIS and ICPs it is extremely difficult to establish modern takaful as a pure Mutual. Thus, takaful in Malaysia is a hybrid, a blend between a Mutual Insurer and an Insurance manager (the Operator).

In Malaysia’s takaful model the Operator provides capital to start the operation and establishes the governance and operating model. Also in Malaysia we operate parallel conventional and shariah compliant financial systems thus for every regulation governing the conduct of insurance we have the equivalent regulation for takaful, and some more. For example, takaful is subject to Bank Negara’s Risk Based Capital requirement suitably modified for takaful but takaful also has additional regulations which insurance does not have. In particular these takaful specific regulations focus on governance as the takaful model can easily create conflicts of interest between the Operator and the participants. The governance structure for takaful currently does not include participants’ involvement in management decisions but instead depends on a complex web of laws (under the Islamic Financial Services Act 2013), regulations (the Bank Negara’s Takaful Operating Framework) and oversight by the Shariah (through each Operator’s Shariah committee and ultimately the decisions of Bank Negara’s supreme Shariah Advisory Committee).

Takaful versus Insurance: Who benefits from the contract?

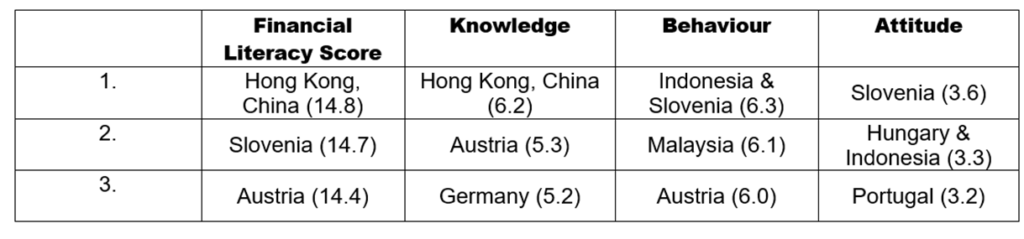

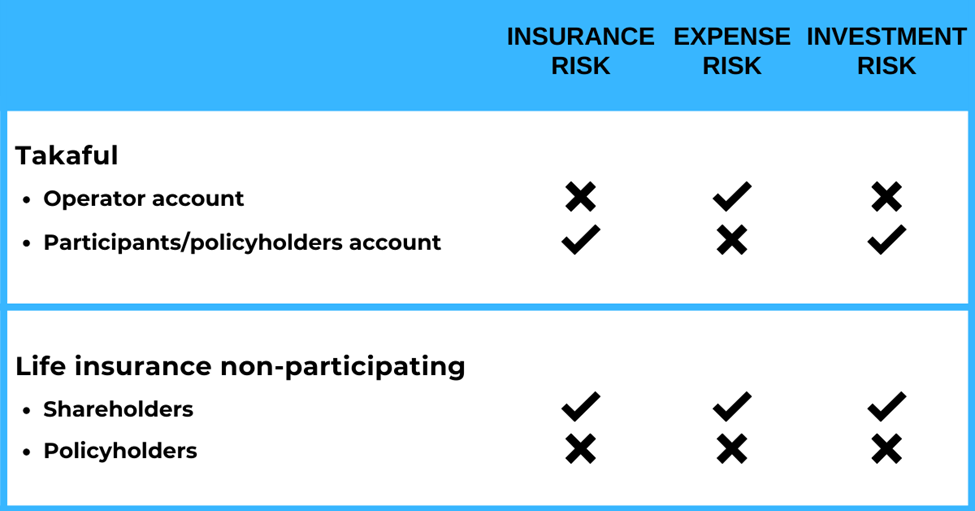

Insurance generally involves pricing of Insurance risk, Expense risk and Investment risk. The table below considers where the various risks reside in takaful and insurance.

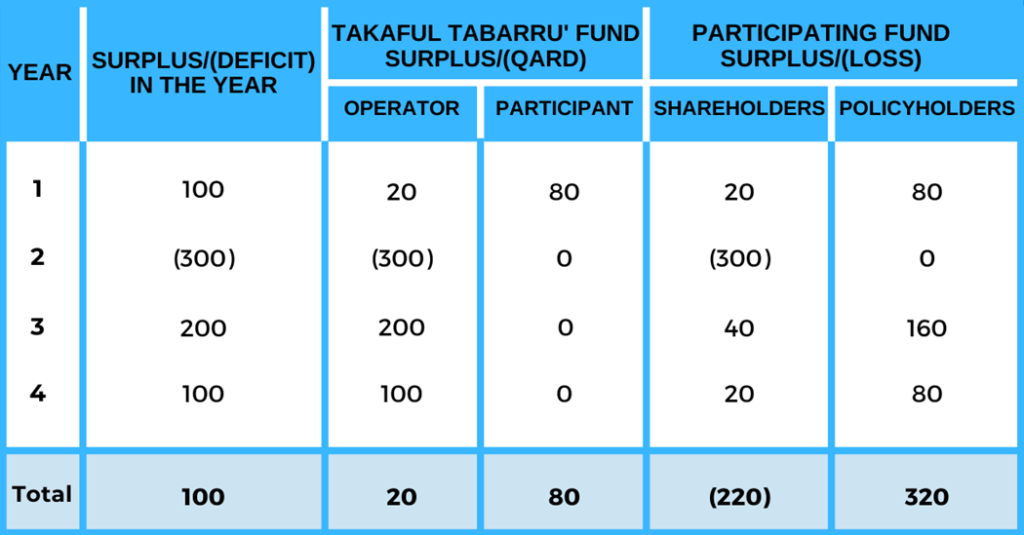

It is clear therefore that unlike in insurance, in takaful the Insurance and Investment risks reside with the participants/policyholders. To illustrate further, the following table provides a numerical example: In the example above it is clear that the economics of the operating model is different between takaful and insurance.

Effectively in takaful, Insurance and Investment profit or losses accrue to participants while Expense profit or loss accrues to the operator. The Takaful Operating Framework does allow the Operator to share in up to 50% of the surplus that is distributable to the participants; however that does not change where the risk resides when actual experience differs from expected. In insurance, the shareholders take all the profit/losses for Insurance, Expense and Investment risks. It is also pertinent to note that takaful products are priced to be competitive to non-participating insurance products. Generally, the actuary does not factor in a “bonus” loading when pricing takaful products, nor would expect future surplus distributions from the Tabarru’ Fund be shown when illustrating takaful products. This is important to consider when determining how surpluses are allocated in takaful.

How are insurance losses treated under takaful and insurance?

Under takaful, if the Tabarru’ Fund is insufficient to cover losses, the Operator transfers a qard (a loan) to the Fund which is repaid from future Tabarru’ Fund surpluses. In insurance the closest equivalent product that can be compared to takaful for this feature is the participating life policy (similar to the with-profits life policy in the UK). Like takaful the participating life fund is maintained in Malaysia as a separate statutory fund, separate from the shareholder’s fund. But unlike takaful the participating life fund does not belong to the participating policyholders. This has been established in law in the UK in the distribution of the Estate in with-profits funds (see precedents in the case of reattribution of the Estate for Aviva and Axa UK). For the participating life fund, the shareholder is also required to make good any deficits in the participating fund by transferring funds from the shareholders fund to the participating fund. However, under the participating life fund operating model there is no provision to repay the shareholders for this transfer. The example below, which assumes a 20:80 (operator/shareholder: participants/policyholders) profit sharing model for both the takaful Tabarru’ Fund and the participating life fund illustrates:

It can be seen from the above that the way the qard works to cover the deficit in Year 2 results in a different economic outcome for the takaful operator as compared to how the same deficit is dealt with in the participating life fund and the resulting financial implications for the shareholders (the deficit is called “Burnthrough costs” for with-profits funds in the UK). The qard in the above example can be considered as a liquidity support from the operator as this qard will be repaid to the operator from the future surpluses in the Tabarru’ fund. In the case of the participating life fund, the shareholders cannot recover the losses from the participating fund in the normal course of business.

The example emphasizes the risk sharing nature of takaful (not just risk sharing among existing participants but also risk sharing between existing and future participants of the Tabarru’ Fund) and the risk transfer nature of insurance (notwithstanding that policyholders share in profits, they are not required to finance any deficits in the participating fund). The reason why in insurance there is a separate statutory participating/with-profit fund is solely for the purpose of managing the allocation of surplus between shareholders and policyholders, 20:80 in the example given above.

Is the operator in takaful ever exposed to insurance risks? In takaful as in insurance there is expected and unexpected (exceptional) losses. The former should be comfortably met by the premiums collected and “earned” in the year while the latter is usually retakaful/reinsured outwards. If the takaful operator is diligent in assessing and implementing its retakaful program and continues to write profitable policies (remember any qard can be repaid from future profits), the operator’s capital would not be expected to suffer economic losses from insurance risks. It should be noted that unlike in reinsurance, in retakaful it is the Tabarru’ Fund that is reinsured, not the takaful operator as the insurance risks reside in the former. This is clear in Malaysia’s Takaful Operating Framework.

The takaful participants’ liability is limited to the premium/contribution that is paid, not to any deficits should the Tabarru’ Fund not be able to meet its claims liability. This is the same for Mutual Insurance where the mutual policyholders’ liability is limited to the premiums paid to the Mutual together with any equity that may have been retained in the Mutual fund. Deficits in the Tabarru’ Fund may also result from operational failures on the part of the operator. Bank Negara guidelines are clear that such losses are for the account of the operator and injections to the Tabarru’ Fund to cover deficits arising as a result of the operator’s operational failures cannot be considered a qard but must be written off by the operator.

Definition of a “contract” under IFRS 17

Finally we consider how to define a takaful contract. As a contract is defined as the smallest unit that should be accounted for under IFRS 17, it is important to define the obligations under a takaful contract or contracts carefully.

As my November note observed, IFRS 17 defines a contract as:

“Contracts can be written, oral or implied by an entity’s customary business practices. Contractual terms include all terms in a contract, explicit or implied, but an entity shall disregard terms that have no commercial substance (i.e. no discernible effect on the economics of the contract). Implied terms in a contract include those imposed by law or regulation.”

IFRS 17 (Paragraph 2) also says “An entity shall consider its substantive rights and obligations whether they arise from a contract law or obligation when applying IFRS 17”. For example in the UK the management of the with-profit life fund business is also subject to the insurer’s Principles and Practices that it adopts (the PPFM) which is not explicitly outlined in the contract itself. The PPFM would therefore be taken into consideration when determining how to account for with-profits policies under IFRS 17.

Similarly for takaful the operator should consider not just its obligations from contract law but also its other obligations under IFSA 2013, ToF and under the agreed Shariah contracts when interpreting the accounting of takaful under IFRS 17. Of particular interest is the application of the shariah contract of wakala. In Shariah, contracts are predefined. This is unlike conventional where the contract is a document where the obligations of the contracting parties are set out. Shariah contracts are predefined contract types. Just by the contracting parties agreeing on the contract type to apply, the obligations of the contracting parties are clearly defined. For example, in Islamic finance the musyarakah contract defines that the parties to the contract agree to go into a business partnership where profits and losses from the venture are divided according to a predefined percentage. In takaful the wakala contract is an agency contract where the agent (the operator) agrees to manage the Takaful Funds on behalf of the participants for an agreed fee, the wakala fee. It is our understanding that the wakala contract is also a contract in shariah which provides an obligation for the wakil (i.e. the agent, in this case the operator) to act as a trustee for the participants. Given the trust nature of the contract as defined by Shariah, the wakil must at all times act in the best interest of the participants. Furthermore, although the Takaful Funds are under the control of the operator, the operator is not a beneficiary of the Funds (the share of any surplus is termed by Shariah as a performance fee) but effectively holds the Funds in trust on behalf of the participants. This shariah interpretation (which is also supported by IFSA 2013 and the ToF) may have consequences in the way in which the takaful operators’ accounts are prepared.

Recently there was a dialogue between the various stakeholders on the application of IFRS 17 to takaful. It is hoped that this note contributes to the ongoing discussions into how takaful should be accounted under IFRS 17.